Food detection App for Diabetics

Preface

This app was built with a team of three individuals as part of the Final year design project for ECE at McGill University.

Why Track Food?

This project is a branch in a tree of future work for HealthCare Apps. The idea behind tracking nutrition was in order to help diabetics keep track of their total carbohydrate count, but also because the Integrated Microsystems Lab at McGill (IML) (link) is developing a database that tracks the body’s insulin responses to food. The IML want’s to build a closed all-in one solution, where diabetic patients are able to optimize their insulin shots according to the foods they’ve eaten. One branch of the project, is to use ML and image detection to count nutrient intake, where the idea is to use a camera to detect foods and track carbohydrates. The CDC reccomends diabetics count Carbs in order to “make managing blood sugar easier”.1

The App

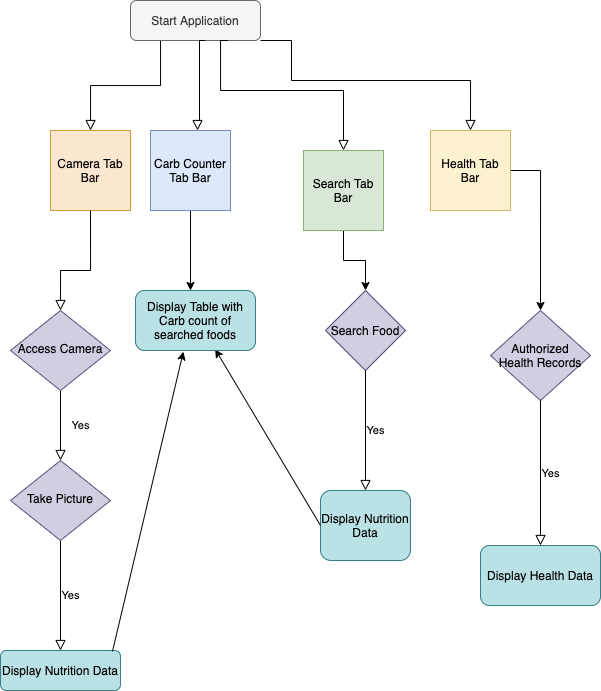

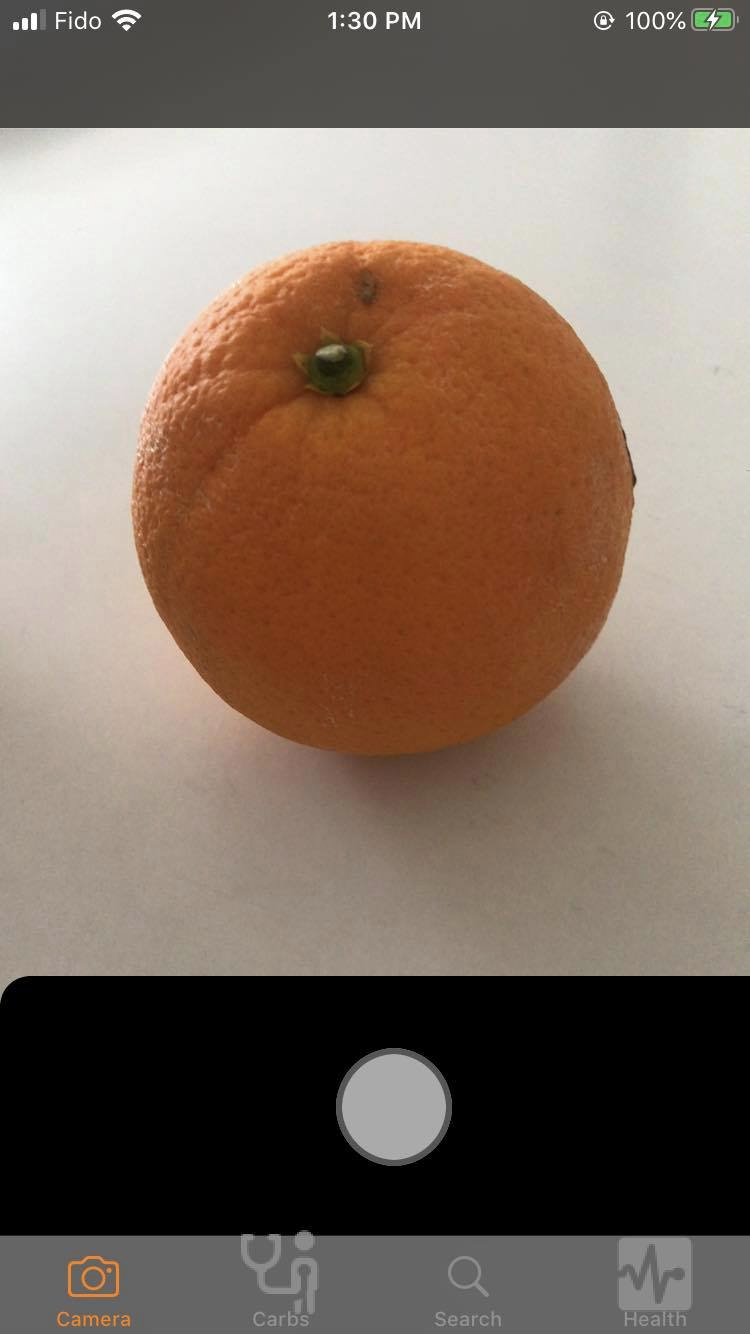

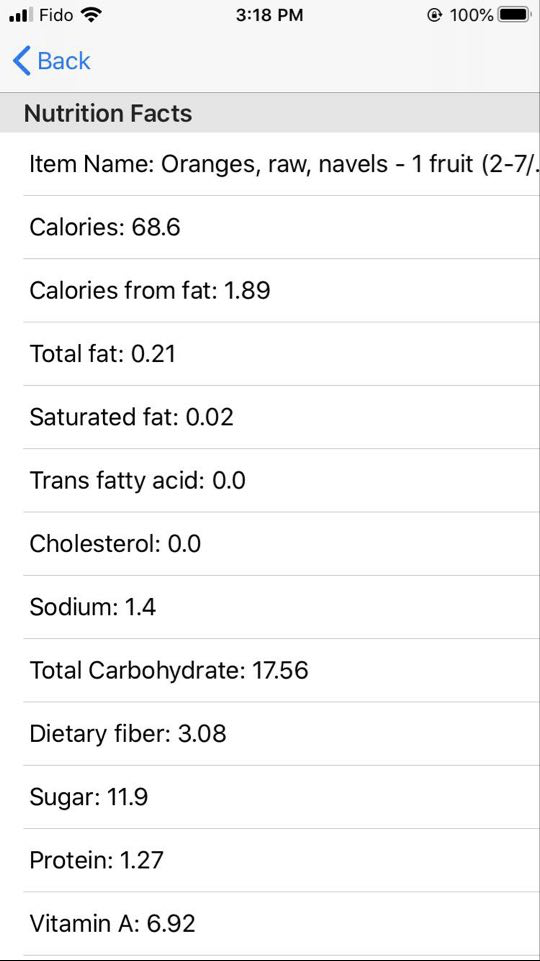

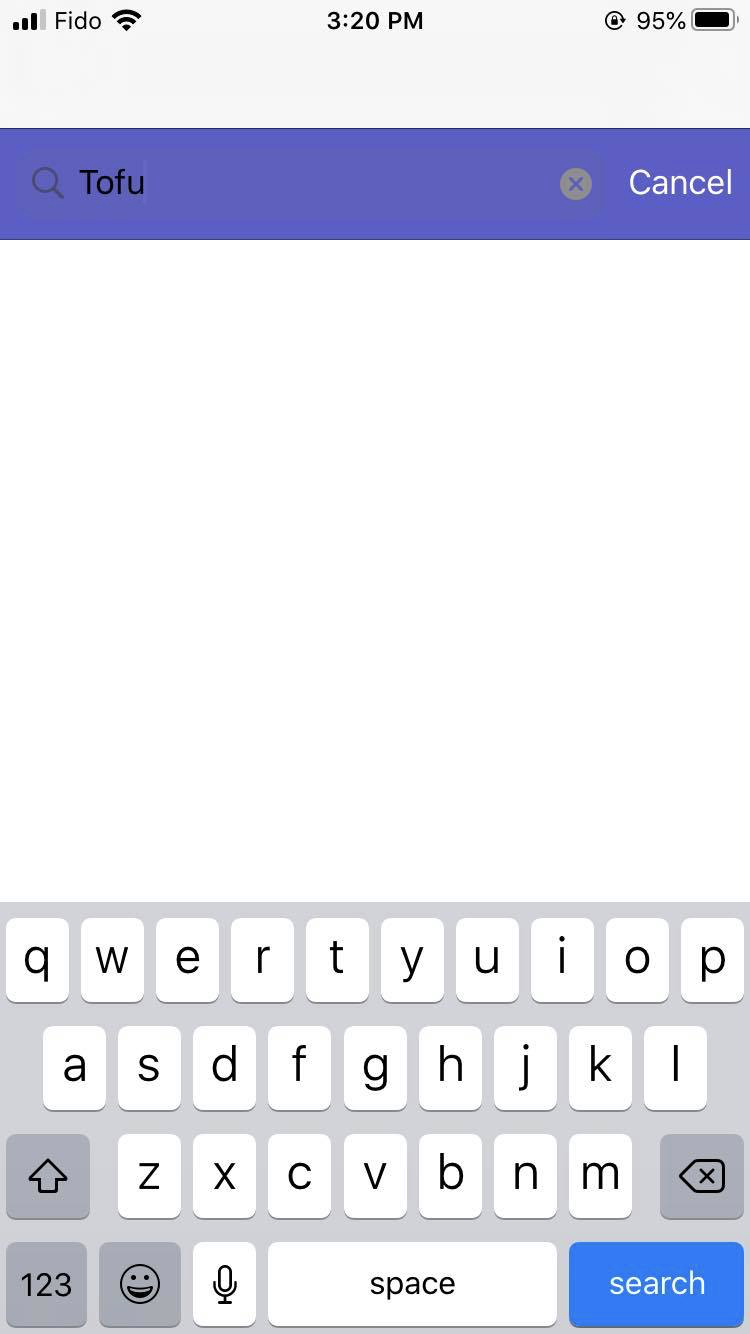

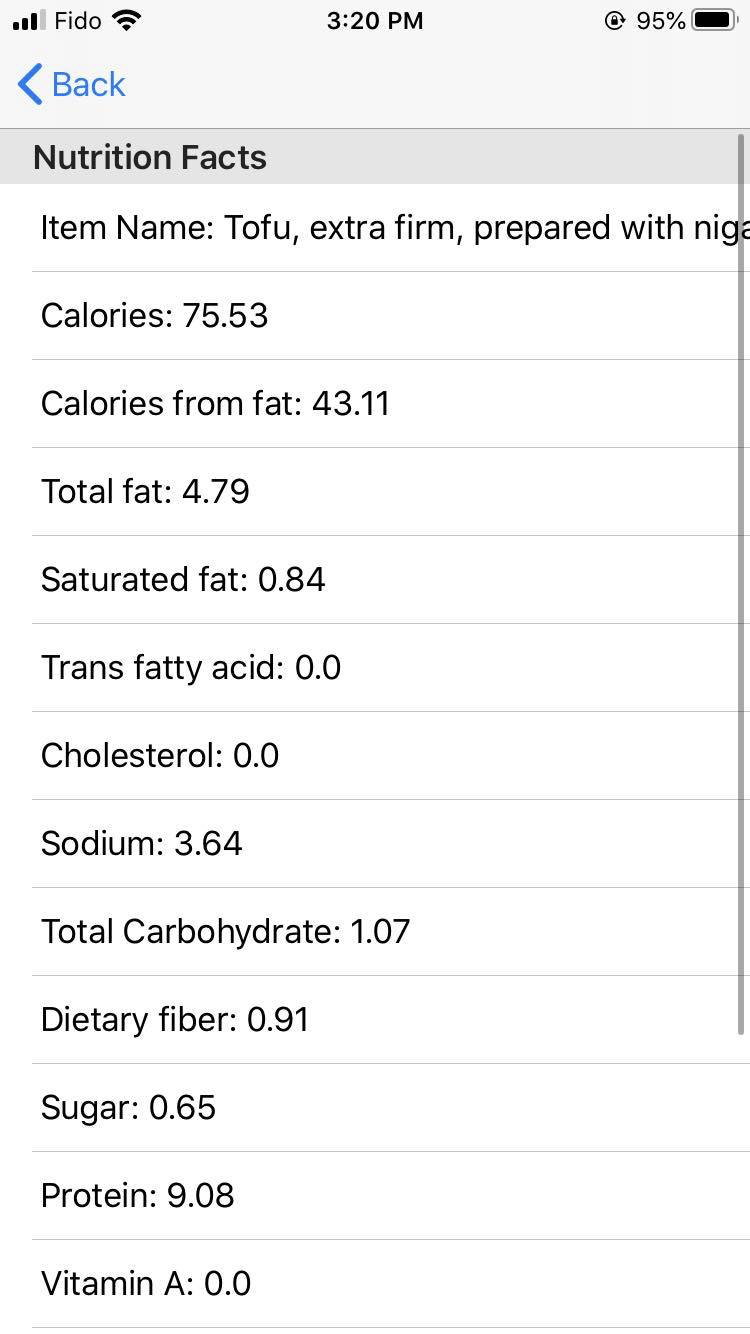

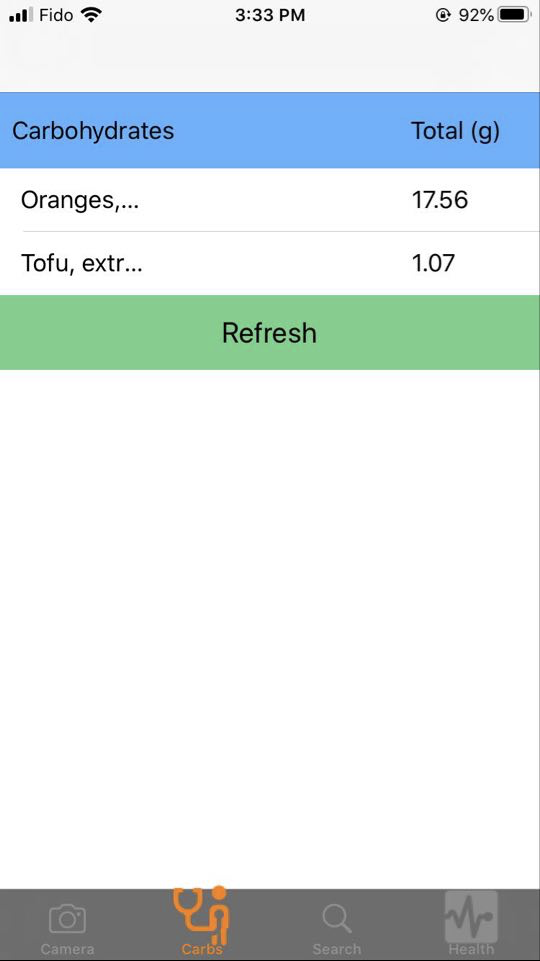

The app is made using SWIFT and CoreML. The architecture of the app is shown in the flow chart above. The four tabs each have specific functions, the camera tab detects the image using a ML Model and the Search Tab requires a text input; after both tabs recieve input they send a JSON query to the Nutritionix API2 which returns the nutritional values of the food items. The carb counter tab takes all of the food inputs and displays them in a list that displays the total and individual carbohydrate content. Here are some of the images illustrating the functionality of the app:

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

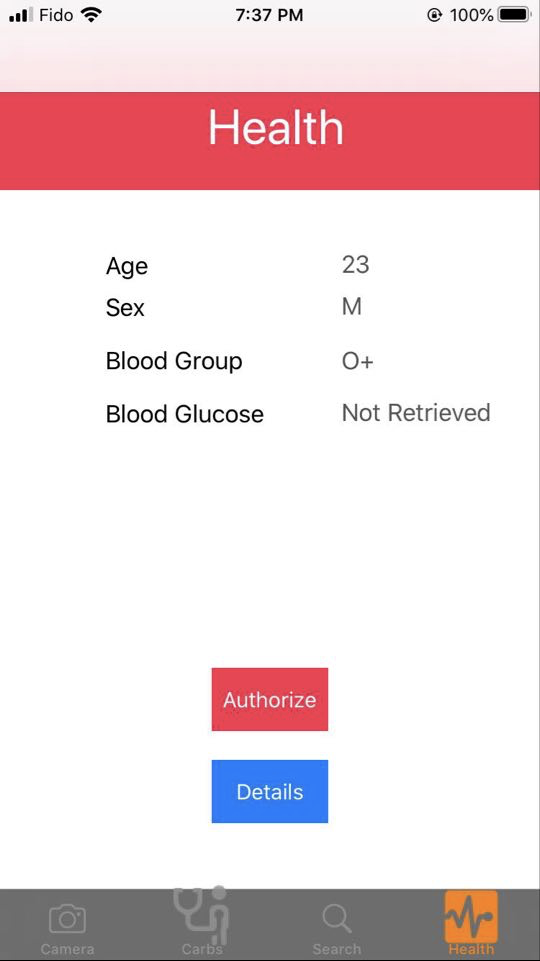

Lastly, the app is integrated with Apple Healthkit, this was done in order to open up the door to further integration of the App with the IML teams insulin database with Apple’s glucose monitoring kit.3

|

|

The app was built to provide an easy to use interface with the user in mind. UI/UX was a priority for our team and every interaction and edge case was taken into account. The team picked up on SWIFT development on the go, therefore the views could have been more smooth, e.g better button placement and color schemes, simpler human-computer interaction (Steve Jobs’ 3 click aproach to accessing iPod songs). There could have also been a greater emphasis on analytics, and the data taken from Apple’s healthkit and food inputs could have been intagrated to provide a more data driven approach to diabetes, which to my best knoweledge, is the next goal of the IML team at McGill.

CoreMl Model

We were given the Food Detection Model in Pytorch and had to convert it to CoreML format. The reason behind using a previous model is that we are interested in mimicking the same architecture used for previous projects in the lab. The conversion was not straightforward, and the team had to train our own model using darknet.

We trained the model using tiny-YOLO as it is faster on devices such as cell phones. We first trained the model on 10 classes from the UECFood100 dataset. Inside the UECFood100 dataset, each folder contains images of a particular class and a text file called “bb_info.txt” where the coordinates of the corresponding food are already present so we do not need to label the images for object detection on our own. We used darknet to train the model and we wrote Python code for the preprocessing step in order to prepare data. Packages used include os and shutil to organize files, and pandas, cv2, matplotlib to remove dirty data as some images need to be rotated to be correctly labelled using the provided coordinates.

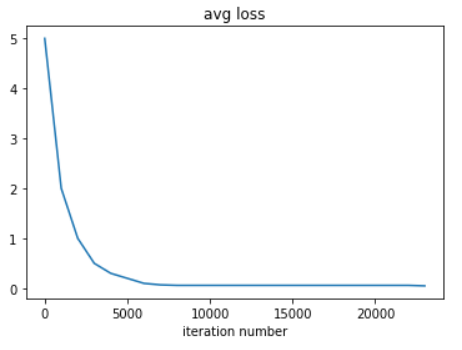

For the training step we used Google Cloud’s virtual machine with a GPU of NVIDIA Tesla T4. The training process took a total of 23,000 iterations. The final model was chosen based on the highest mAP (mean average precision) and IoU (intersection over union) as well as the precision given on the validation dataset to avoid overfitting. The training was stopped when the average loss no longer decreased.

|

|

After training the model using darknet, we used darkflow to convert it from the format of weights to the format of pb. Then we used tf-coreml to convert the model to Core ML. When using tf-coreml, it is necessary to set a few parameters that correspond to the training method used. In our case, the channel color must be set to RGB and the weights are normalized in the range from 0 to 1 so the image scale needs to be set to 1/255.0. If those parameters are missing, the Core ML would generate incorrect predictions.

Given time constraints the model could not have been trained on more datapoints and on a larger dataset, however the model was large enough to demonstrate basic functionality of the app.

Conclusion

At the end the team was satisfied by the functionality of the app. There were some improvements that would have increased the utility of the app, such as a more comprehensive CoreML model that is trained on a larger dataset, more user driven analytics and a better UI model. The main takeaway for our team from this project is that the application we have built is more complex than the majority of iOS apps, mainly due to conscious design with the user in mind. Lastly, the team learnt that we are able to build tools that further developments in our society, it just requires a passion for problem solving. In this case we are able to progress developments that aid Diabetic patients.

You can see the final report here

-

“Carb Counting, Eat Well with Diabetes.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 19 Sept. 2019, www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/eat-well/diabetes-and-carbohydrates.html#:~:text=On average, people with diabetes,(60–75 grams). ↩

-

“Nutritionix API.” Nutritionix, https://www.nutritionix.com/business/api. ↩

-

Apple Inc. “One Drop Chrome Blood Glucose Monitoring Kit.” Apple Developer, https://www.apple.com/shop/product/HMN02LL/A/one-drop-chrome-blood-glucose-monitoring-kit. ↩